It can be difficult knowing how to increase student motivation in your online course. But online learning has a ton of ways to raise engagement and students’ motivation! This article focuses on the ways that providing kinds of personalized feedback can ensure your students are getting the resources and comments that best address their needs.

How to Use This Article

Use the following article in the way best suited for your needs:

- Read Step 1 if you want the most important information and a simple example. This is for faculty who just want the abstract or are looking for an easy way to improve their instruction.

- Also read Step 2 if you want to implement more advanced personalized feedback. This is for faculty who want to improve their quality of feedback and want more than the basics.

- Continue to Step 3 if you want to learn more about using personalized feedback throughout your course, beyond just assignments. This is for faculty who are open to changing different parts of their course. Your instructional designer can help you incorporate personalized feedback into your course!

Step 1: Introduction to Personalized Feedback

Personalized feedback is not new. Grades and comments from instructors are foundational in any course. But effective feedback should be more personalized than a letter grade or a simple “Nice job!” or “Try again!” Providing adaptive and personalized feedback can help students perform better in the course, become more self-regulated learners, and stay motivated to complete the coursework (Maier & Klotz, 2022). Plus, students prefer personalized feedback over general comments (Cramp, 2011), and it motivates them to put more effort into a course.

Teaching a large survey course, an asynchronous online course, or both limits how realistic it is to provide personalized feedback to all learners on all learning tasks (Planar & Moya, 2016). Still, feedback is crucial for helping students learn, improve their capabilities, and become effective practitioners in their fields. Furthermore, offering timely feedback can be a challenge too, but it is critical for the learning process that feedback comes just in time for students to practice and improve their skills.

The Best Feedback Is Formative

Feedback is most effective when it comes during the learning process rather than at the end (this is the difference between formative and summative assessments). Giving timely and constructive feedback helps learners improve their knowledge and skills while practicing them before they are assessed for a summative grade. Consider having students submit drafts of their work so you can reinforce strong skills or correct misconceptions early. Another advantage of formative feedback is that there is no grade attached. Detailed feedback tends to be skipped when a summative grade is provided as well (Underwood, 2008).

One important characteristic of strong formative feedback is its actionability. Students should be able to take feedback and immediately know how to use it to improve their work. Reference the criteria for success for the assignment or the overall learning goals of the course when giving specific, actionable feedback as well.

Finally, provide a method for students to engage with the feedback. Develop a way for students to ask follow-up questions based on the comments and suggestions for improvement. Students’ reactions can also inform the instructor on the best ways to provide feedback, especially critical or constructive comments, moving forward. Try offering to meet to discuss the feedback during office hours that week, or even include a link for students to schedule an appointment with you directly in the feedback you provide.

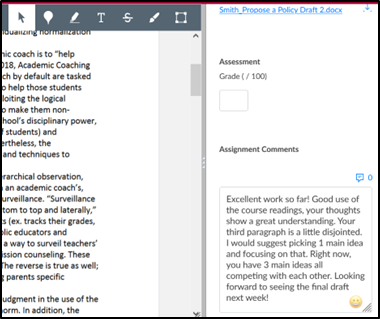

An Example of Personalized Feedback

The most common form of personalized feedback in Canvas is probably the SpeedGrader comment. While using SpeedGrader, instructors have access to a comment box where they can provide praise for excellent work and suggestions for revisions or edits to improve their work. There, instructors can provide summaries of their feedback, explanations of their overall grades, or links to resources. The image below shows an example of a comment on a draft of a research paper. The comment helps the student identify their strengths and their weaknesses in a succinct manner. Ideally, the comment is paired with more in-depth comments within the paper itself.

Step 2: More Advanced Personalized Feedback

Personalizing suggestions for improvement and praise for student work sounds easy enough, but a serious gap between students’ expectations for feedback and what instructors give is unfortunately common. Carless (2006) identified a discrepancy between the students’ and instructors’ perceptions of how detailed feedback is. Instructors tend to overestimate how detailed and useful their comments are compared to how their students perceive those same comments. One cause of the discrepancy is that students often don’t understand the feedback because they can’t decipher how to use it to improve their work (Planar & Moya, 2016). The feedback coming too late to be useful for students’ learning is another problem (McConlogue, 2020).

In order to be effective, feedback should address multiple components of the learning task and process (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). When providing high-quality personalized feedback, consider the following five areas:

The task: What is the student doing or producing?

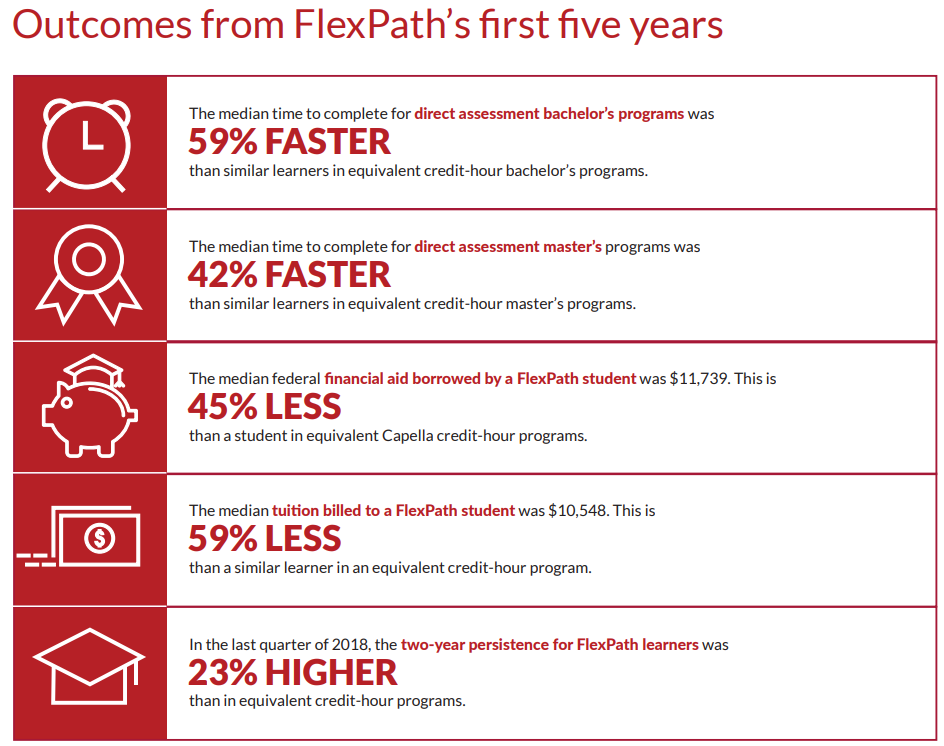

Different disciplines require different types of feedback. Is the student’s work authentic and realistic to the field of study? If proficiency in a particular skill (e.g., MS Excel calculations or pronouncing words such as in the image below) is important, the feedback should focus on correcting errors or misconceptions that could lead to errors. In the example below, the instructor could record themselves correcting a mispronunciation. On the other hand, more abstract thinking requires feedback to focus on concepts like organization and sequencing of thoughts and the connections between ideas.

In addition, the feedback should help students produce authentic artifacts of learning or act like a practitioner in the field. Instructors often do such when teaching citation styles, but feedback could also include information on how to effectively present information in a meeting, use appropriate scientific notation in a lab journal, or write a methods section in an ethnographic study.

The processes: Does the student think and work like a practitioner? How is the student evaluated?

When preparing a presentation at a business meeting, conducting a scientific experiment, or participating in an ethnographic study, are students doing so in the most effective, authentic way? Feedback throughout the processes of learning can help correct procedural errors or misconceptions in a student’s way of thinking.

Further, are students practicing the skills or using the knowledge they need for their assessments? Feedback can help identify the ways students can improve their work to better align with the criteria for success outlined in the course.

Self-regulation: How well does the student plan, set goals, seek help, manage time, etc.?

Feedback can be a powerful tool for helping students reflect on their self-regulation skills. If the quality of their work suffers as a result of poor time management or a lack of planning out their work, students can find feedback helpful in that regard as well. Suggest ways that students can utilize tools (ideally ones that would be accessible or even expected in the field) to perform more effectively. Improving self-regulation is a great benefit of personalized feedback (Wang & Lehman, 2021; Maier & Klotz, 2022). Student motivation and engagement also benefit from more robust self-regulation skills (Planar & Moya, 2016).

The student: How well does the instructor know the student?

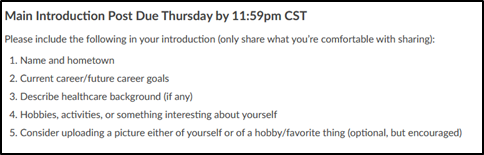

Knowing the student (their goals, career aspirations, prior experiences, content knowledge, etc.) is helpful for personalizing feedback. The example pictured below shows instructions for an introductory discussion post in which students describe themselves, including their current careers or career goals. The instructor can then use that initial discussion board to reference this information about students when providing feedback relevant to their careers. It can be greatly motivating for students to revise and improve their work when they see the benefit to their goals or future, or when they feel the instructor is invested in their success.

The relationship: How does the instructor work with the students?

The way instructors understand their role in the learning process affects the quality and the results of the feedback they give. Students are not motivated by feedback from instructors with an authoritative, controlling presence in the course (McConlogue, 2020). A relationship built on mentorship provides more motivating feedback, whether it’s praise or constructive criticism.

Personalized feedback also greatly benefits students from underrepresented or marginalized groups, especially during their first year in college (Espinoza & Genna, 2021). Having a positive relationship with faculty is a great motivator for students who cannot rely on family or friends to help them navigate the (often unspoken) norms of higher education. In these instances, personalized feedback from instructors is even more important.

Step 3: Personalized Feedback Beyond a SpeedGrader Comment

Thank you for investing in improving the quality of your feedback! By reading this section, you will be well positioned to provide high-quality personalized feedback, even beyond the comment box of SpeedGrader. There are many ways you can offer positive and constructive comments throughout your course.

Audio and Visual Feedback

The written word just doesn’t provide as much information as quickly as the spoken word. A video can convey tone, body language, and facial expressions while the instructor is speaking. In addition, feedback is best delivered in a similar cadence as the student’s work, so a video or audio clip could be more appropriate than a written comment, such as for a foreign language or art course. You might find that students respond more to video recordings of your comments than typed ones, and the video comments might be faster than typing them, anyway!

Canvas SpeedGrader allows you to upload audiovisual files into the grading interface. In 2022, Canvas also integrated the use of emoji into the comment box, which could be an easy way to visually share your tone without recording an audiovisual file.

Performance Recording Comments and Suggestions

Beyond recording a video of your comments, you might upload a video of you providing feedback on a student-uploaded video! For instance, if you were the instructor of a course on public speaking, you might record yourself with the student’s recorded speech, pausing their recording to offer praise and suggestions for improvement. A computer science instructor might have a student who is having trouble with some software record their screen when they encounter the problem, then the instructor can record a video on how to fix that problem!

Product Comments, Edits, Revisions, and Annotations

Within Canvas, instructors are not limited to the comment box within SpeedGrader. When students submit documents or files, instructors can download them and offer comments, edits, revisions, and annotations within that file (e.g., a Microsoft Word document or a Google Spreadsheet). Then, the instructor can re-upload the annotated and revised version of the student’s work to SpeedGrader for the student to review.

Email Check-Ins

Whether scheduled or only on an as-needed basis, reaching out to students through email is a great opportunity not only to develop a strong relationship with them but also to provide them with personalized feedback. Instructors can offer praise or suggestions for improvement based on recent student submissions or reach out with advice or their own experiences to connect with students and motivate them further.

Announcements

While not everyone loves this, many people appreciate a public shout-out for good work! Instructors can use the Announcements feature in Canvas to highlight great work, strong effort, and effective collaboration (or any other positive behavior the instructor wants to see in their course). A weekly announcement that instructors post to improve their presence in the class, connect materials to current events, and/or provide important time-sensitive information can also add a “Student Shout-Out” section. It might be worthwhile to reach out to the student beforehand to get their permission to give them the shout-out, as sometimes public praise can be demotivating for people.

“Message Students Who…”

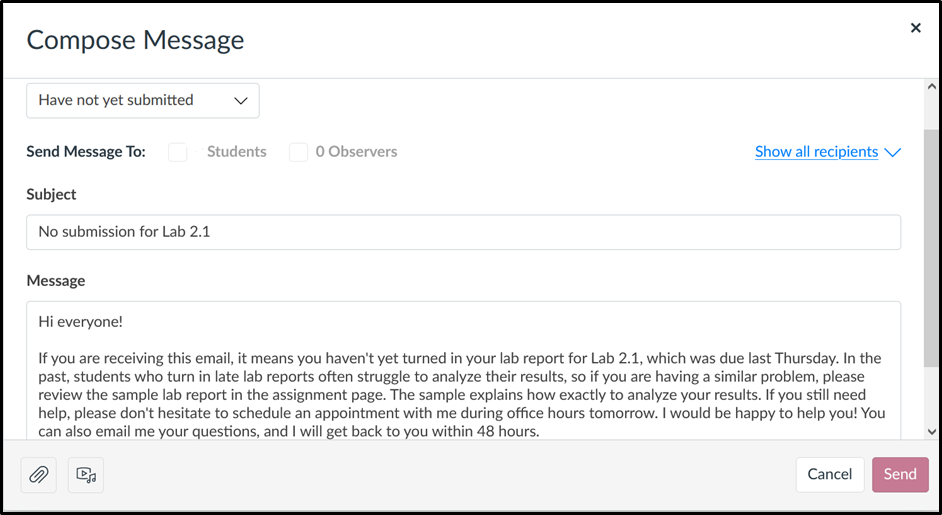

Canvas makes it easy for instructors to reach out to students according to certain criteria, such as those who earned a specific grade, haven’t yet started an assignment, or had the assignment reassigned to them for revisions. Canvas will dynamically change the address list, but you have to supply the email subject line and body of the message. The message itself is where you can include feedback specific to each group of students. For example, in the image below, the instructor is messaging all the students who have not yet turned in their assignment, including reminders of their office hours and how students can contact them with questions or concerns they have in the email.

Discussion Boards

Designing an effective discussion board assignment involves more work than just requiring a post and a comment (Berry, 2022). A strong discussion board assignment can facilitate the opportunity for students to provide personalized feedback to each other! If they know the criteria for success and appropriate norms for providing constructive criticism, a peer’s feedback can be a powerful tool for improvement.

Peer Review

Students themselves can provide important feedback to each other, not only in written comments but also through comparisons between work and norms established by the instructor. Students who review a peer’s work not only assess their peer’s submission against the instructor-provided rubric but also compare their peer’s work against their own. Further, by using the rubric as an instructor might, students are getting important perspectives on how rubrics can guide their work. This kind of feedback is especially useful for students, as they often don’t take the perspective of the instructor very often. Finally, the actual written comments students provide each other can be useful, as they can include perspectives or feedback the instructor might not.

Contribute to This Article

If you have a great example of any of the forms of personalized feedback, we would love to share it with our instructors to help make each course at UW Extended Campus as excellent as possible!

In addition, let us know if you use a way of sharing personalized feedback not mentioned in this article. It could be the next innovative spark to help someone else level up their students’ motivation.

Email Brian Chervitz at brian.chervitz@uwex.wisconsin.edu with your ideas.

References

Berry, L. (2022, July 15). A framework for increasing critical thinking, student engagement, and knowledge construction in online discussion. IDigest. https://ce.uwex.edu/a-framework-for-increasing-critical-thinking-student-engagement-and-knowledge-construction-in-online-discussions/

Carless, D. (2006). Differing perceptions in the feedback process. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 219–233. http://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572132.

Cramp, A. (2011). Developing first-year engagement with written feedback. Active Learning in Higher Education, 12, 113–124.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. http://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487.

Maier, U., & Klotz, C. (2022). Personalized feedback in digital learning environments: Classification framework and literature review. Computer and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100080.

McConlogue, T. (2020). Assessment and feedback in higher education: A guide for teachers. UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv13xprqb.2.

Merry, S., & Orsmond, P. (2008). Students’ attitudes to and usage of academic feedback provided via audio files. Bioscience Education, 11.

Planar, D. & Moya, S. (2016). The effectiveness of instructor personalized and formative feedback provided by instructor in an online setting: Some unresolved issues. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 14(3), 196-203.

Underwood, J. S., & Tregidgo, A. P. (2008). Improving student writing through effective feedback: Best practices and recommendations. Journal of Teaching Writing, 22(2), 73-97.