It can be difficult knowing how to increase student motivation in your online course. But online learning has a ton of ways to raise engagement and students’ motivation! This article focuses on the ways that providing kinds of instant feedback can ensure your students are getting the resources and comments they need at the moment they need them.

How to Use This Article

Use the following article in the way best suited for your needs:

- Read just Step 1 if you want the most important information and a simple example. This is for faculty who just want the abstract or are looking for an easy way to improve their instruction.

- Also read Step 2 if you want to implement more advanced instant feedback on an assignment. This is for faculty who want to improve their quality of feedback and want more than the basics.

- Continue to Step 3 if you want to learn more about using instant feedback throughout your course, beyond just quizzes. This is for faculty who are open to changing different parts of their course. Your instructional designer can help you implement instant feedback in many parts of your course!

Step 1: Introduction to Instant Feedback

Timely feedback for students is integral to effective learning and students’ satisfaction with their learning experiences (Espasa & Meneses, 2010). Providing that feedback, however, can be more difficult in online classes. Although your lack of physical proximity to your students can be challenging, your feedback remains essential. It can be a powerful tool for motivating students through online courses, especially instant feedback (Bridge, Appleyard, & Wilson, 2007).

Instant feedback could include praise for excellent work, corrections of mistakes, or helping a student assess the quality of their work and assess the pace of their learning.

Instant feedback provides several benefits for students:

- Mistakes and misconceptions can be immediately corrected.

- Correct knowledge and skill application can be positively reinforced.

- Corrective feedback can be personal, which avoids embarrassing students.

- Students gain more self-awareness of strengths and gaps in knowledge or skill sets.

- Instant feedback can increase the amount of time a student is engaged in the course.

Two Types of Instant Feedback

In an online course, students can benefit from two kinds of instant feedback: instructor comments and norm-referenced feedback. Norm-referenced feedback is feedback students get by comparing their work or progress to other examples or standards, often created by the instructor. For instance, giving students an example of an exceptional essay to help them with their essay is providing norm-referenced feedback. Both instructor comments and norm-referenced feedback are common in coursework, though the latter form may not be immediately recognized as instant feedback.

Instructor Comments

You can provide automatically generated written comments in response to specific answers or behaviors provided by students. For instance, when students choose an incorrect answer on a quiz, you can set up an automatic comment to provide the student with the necessary resources to fix their mistake the next time they need that knowledge (for example, in an assignment or exam).

Norm-Referenced Feedback

Students don’t just receive instant information from their instructors in the form of comments in response to answers. If you provide your students with norms for the class, such as deadlines, suggested timelines, and models of good work (and examples of poor work), they can compare their work and learning progression with those norms. They can instantly recognize when they are falling behind, need to improve their answers, or need to complete specific, upcoming work, all as soon as they need it.

Example of Instant Feedback in Canvas

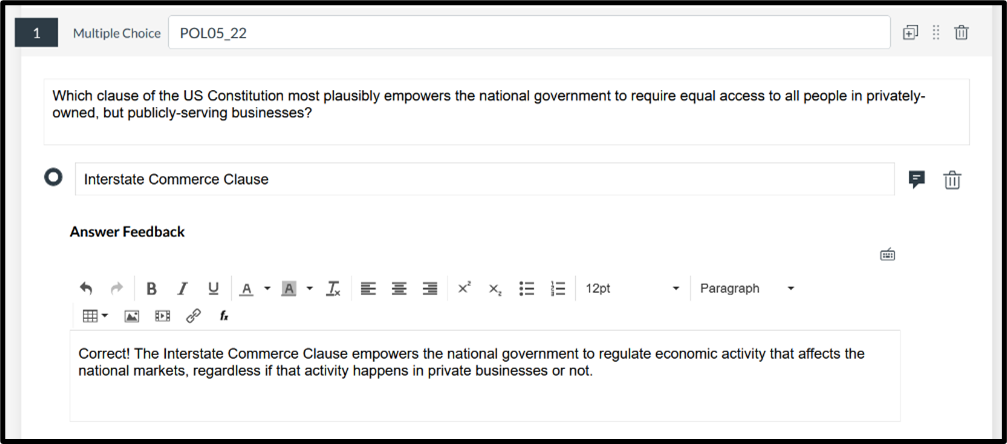

In this political science course, the instructor set up a Canvas quiz to automatically provide feedback based on a student’s answer. In the first image, the correct answer provides positive feedback.

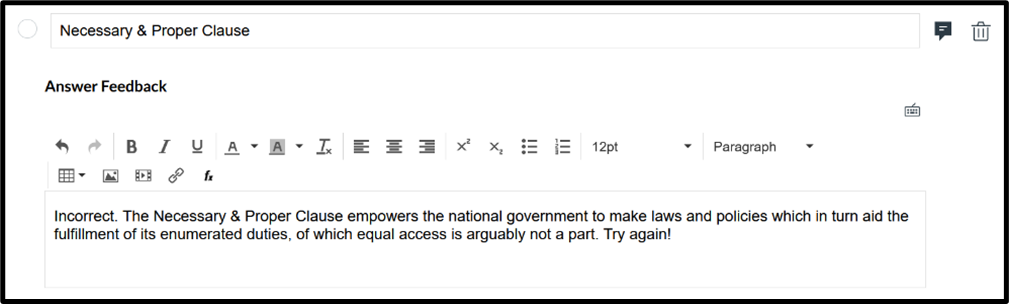

In the second image, an incorrect answer provides instant feedback as well, explaining the likely misconception that would lead a student to choose that answer.

Step 2: More Advanced Instant Feedback

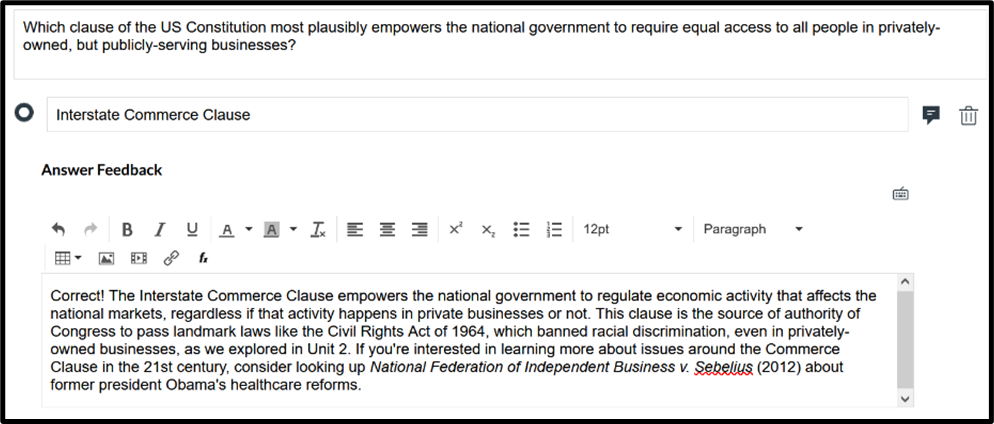

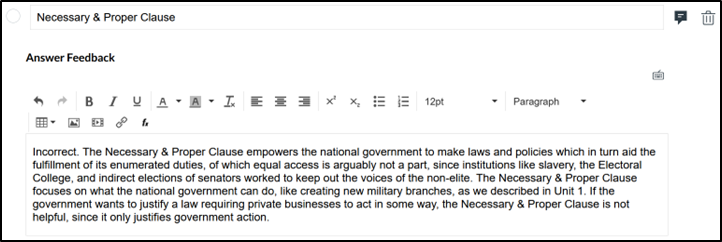

Thanks for striving to improve your feedback! While any helpful feedback is better than no feedback (Espasa & Meneses, 2010), there are ways to improve its quality and effectiveness. The third and fourth images below show more detailed feedback for both correct and incorrect answers, demonstrating the characteristics of effective feedback.

Make Your Feedback Descriptive

Explain why the correct answer is correct and why the incorrect answer is incorrect. Consider some mistakes that students often make when trying to identify the correct answer. Address the misconceptions that could lead a student to one of your distractor answers. In norm-referenced feedback, provide specific, measurable parameters and expectations.

Make Your Feedback Actionable

Provide concrete information about how students can improve their knowledge or skill or how they specifically succeeded in accomplishing a goal. This is also a great opportunity to connect the knowledge or skill to prior experiences or future conditions in which the students would use that knowledge or skill.

Make Your Feedback Empowering

Empower students to assess their own answers by showing them how to confirm their answers as correct or not. Reinforce the connection to the overall learning objectives of the course to help students evaluate if they are on track to achieve their goals or not. In addition, you can use the feedback to offer resources to deepen students’ learning and extend their understanding of current events or passion projects if they are meeting expectations already.

Step 3: Instant Feedback Beyond the Quizzes

By reading this section, you will be well positioned to make your course as excellent as possible! Canvas quizzes are a natural tool to provide instant feedback because Canvas quizzes have a built-in feedback feature! But implementing instant feedback in other parts of your course can help motivate your students as well.

Instructor Comments

Synchronous Meetings

Meeting with a student during office hours is another great way to instantly provide feedback by providing guidance on any trouble the student may be having, by sharing personal experiences to help the student see their learning in a new way and build a relationship with them, or by giving a student the next steps to deepen their knowledge or skills.

Synchronous feedback can come from peers as well. If your course easily facilitates group work or large group meetings, students can get instant feedback from their peers by having their questions answered or get different perspectives on tough problems, case studies, or scenarios, or just the notes and concepts of the course.

Acknowledgments of Achievement

With the right third-party tool, such as Badgr, integrated into your Canvas course, students can instantly earn badges as an acknowledgment of their achievements. Badges can provide positive feedback when a student completes a module or an important milestone in the course. You can use badges to assess students’ progress in the course as well, not just to recognize their final achievements.

Frequent Polls

This strategy uses Canvas’s quiz engine, so it may not seem like it’s really “beyond quizzes”; however, quizzes don’t have to always be used in the traditional way. Creating a unique question or poll for your students to check in every once in a while can be a great way to provide instant feedback and thank students for engaging in the class and congratulate them for getting their work done.

Adaptive Learning Paths

It’s possible to create adaptive learning paths using Canvas quizzes. This means that you can create differentiated learning experiences based on a student’s performance on a quiz. The quiz could be at the beginning of a module and could adapt based on the degree of success or student interest. The quiz could be in the middle of the module as an informal assessment of students’ progress, and either direct a student forward through the module for doing well or back to previous learning resources to practice more and try again.

Norm-Referenced Feedback

Sample Answers; Practice Assignments; Past Submissions; “A”, “C”, and “F” Examples

Whether your assignments are typically practice problems, case studies, research papers, or performance demonstrations, you can utilize sample answers or models to explicitly show your expectations for the assignment. Students can compare their own ideas with the sample answers provided in a similar (but not identical) assignment or practice assignment. Alternatively, they can compare their assignment submissions to the model or to the examples of excellent and poor work you provided and get feedback that way.

In the image below, the instructor recorded a video of his feedback on previous students’ works, which current students can use as a norm with which to compare their own work.

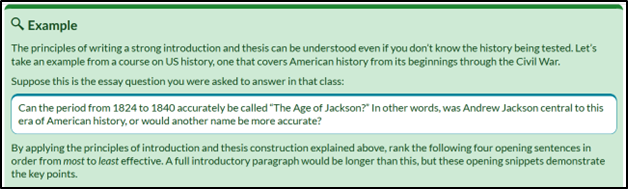

In the following example, students were provided a hypothetical essay question and then four opening sentences to rank in order of most to least effective. After the students ranked them for themselves, the instructor provided their own comments on each sentence’s effectiveness. Students could see whether their list aligned with their instructor’s expectations or not.

Peer Review

Similar to the strategy above, peer review can be a great tool for students not only to provide (albeit) delayed feedback to a peer but also to get instant feedback on their own work by comparing it to their peers’ work. By using the grading rubric with a peer, students get an immediate perspective on how their own work might be evaluated through that same rubric.

Self-Feedback from Reflection

Reflection questions after a demonstration, reading, video, or any other learning experience can elicit self-feedback from students. They can ascertain whether they have made progress toward the learning objectives after completing the learning experience by answering specific guiding questions written to connect the learning resource and the overall goal(s) of the lesson or course.

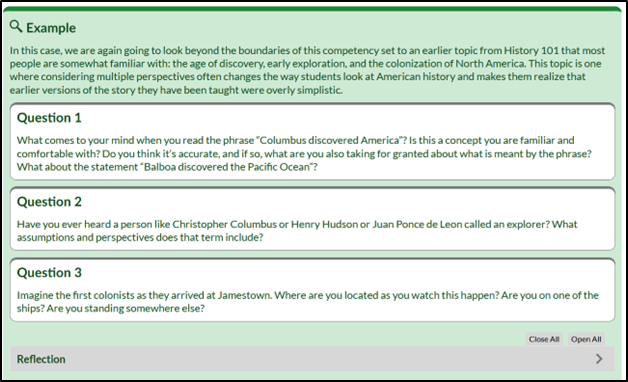

In this example, a history instructor provides self-reflection questions for students to help them practice their historical skills in perspective-taking and critical analysis.

In addition, feedback doesn’t have to be words or comments. By providing a timeline or pacing plan for your course or even just individual assignments, students can get instant feedback on their progress based on their work relative to the timeline. UW Flexible Option incorporates suggested timelines in all their courses in case a student wants a norm to help them pace themselves through the course.

Progression Signposts

Have your students completed half of their coursework? Did they just finish assessing for the first learning objective? Let them know! A progress bar is a great way to visually show progression through a lesson or a course, but short callouts or images can convey progression as well.

Total Points Grade

Rather than grading students with percentages, in which everyone starts with 100% and tries to maintain a strong average grade, instructors can change their Canvas gradebook to Total Points. Total Points starts all students at 0, and they gain points as they complete their coursework. The syllabus can define the minimum points required to achieve a particular grade, and students can immediately see how far off they are from their goal, which provides feedback on how on- or off-track they are from their goals.

Assessment Previews

Knowing how a student will be assessed helps them stay focused on their most important learning experiences, as well as allows students to evaluate their preparedness for meeting the learning objectives. Allowing students to preview the assessment (whether that includes a “peek” at some details or the entire task depends on the assessment) gives students instant feedback on their progress and the effectiveness of their learning.

Leveled Assignments

Meeting learning objectives is the ultimate goal of any course, but some students might be interested in deeper learning. Or perhaps the instructor has expertise in a particular sub-topic in the course and desires to engage students in learning above and beyond the learning objectives. Providing optional, suggested, or aspirational assignments that dive deeper into a complex, relevant, and engaging topic or project also gives students instant feedback on their level of knowledge and achievement toward the learning objectives. How prepared are they for the tougher projects? In addition, you could praise students directly in the optional assignments for attempting (or even looking at) the more challenging work, even if they don’t finish. If they do succeed, that’s another reason for positive feedback!

Contribute to This Article

If you have a great example of any of the forms of instant feedback, we would love to share it with our instructors to help make each course at UW Extended Campus as excellent as possible!

In addition, let us know if you have a way of sharing instant feedback not mentioned in this article. It could be the next innovative spark to help someone else level up their students’ motivation.

Email Brian Chervitz at brian.chervitz@uwex.wisconsin.edu with your ideas.

References

Bridge, P., Appleyard, R., & Wilson, R. (2007). Automated multiple-choice testing for summative assessment: What do students think? Paper presented at the International Educational Technology (IETC) Conference, Nicosia, Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED500077.pdf

Cavalcanti, A. P., Barbosa, A., Carvalho, R., Freitas, F., Tsai, Y., Gašević, D., & Mello, R. F. (2021). Automatic feedback in online learning environments: A systematic literature review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666920X21000217.

Debuse, J., Lawley, M., & Shibi, R. (2007). The implementation of an automated assessment feedback and quality assurance system for ICT courses. Journal of Information Systems Education, 18(4), 491–502.

English, J., & English, T. (2015). Experiences of using automated assessment in computer science courses. Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice, 14, 237–254. Retrieved from http://www.jite.org/documents/Vol14/JITEv14IIPp237-254English1997.pdf.

Espasa, A., & Meneses, J. (2010). Analysing feedback processes in an online teaching and learning environment: An exploratory study. Higher Education, 59(3), 277–292. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25622183.

Ross, B., Chase, A., Robbie, D., Oates, G., & Absalom, Y. (2018). Adaptive quizzes to increase motivation, engagement and learning outcomes in a first year accounting unit. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15. Retrieved from https://educationaltechnologyjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41239-018-0113-2.

Simkins, S. P., & Maier, M. H. (2010). Just-in-time teaching: Across the disciplines, across the academy. Virginia: Scott Stylus Publishing, LLC.