Introduction

Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. Three small words with huge meaning! So what do these words mean to our Instructional Design team? They mean creating courses where students see their lived experiences valued and represented and space for their voices to be heard. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to developing courses with an equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) perspective. What this looks like varies from subject to subject and course to course.

EDI can sometimes feel like an all-or-nothing task. It may feel overwhelming to figure out where to start or how to incorporate it into your course. In that regard, EDI is no different than other course design principles. For example, you may start your course development with one or two really engaging, dynamic discussions or one authentic assessment. And that is great! When the next revision comes around, you may find another assessment to modify or resource to update. EDI is similar. The challenge with EDI can sometimes be where to start. To help, we’ve created the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Reflection Document. This document can be used during new course development and revisions to help identify areas where EDI is incorporated well and areas where it could be improved. From that information, we create an EDI action plan for your course.

An Example of Using the EDI Reflection Document

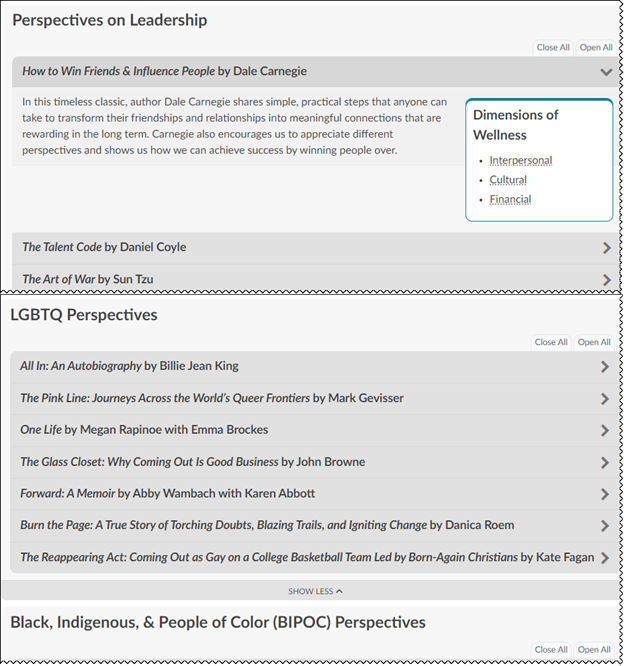

A recent example of how to use this document comes from Lifetime Wellness and Self-Growth, a course that is part of the Collaborative AAS program. Chris Jones (Lecturer of Kinesiology at UW-Eau Claire – Barron County) and I started off the course development by looking at what he wanted to do, where EDI was present in the course already, and where there were opportunities for improvement. One area Chris identified early on was the list of resources provided to students for a semester-long project in the course, the Self-Growth Book Review. Early in the semester, students are given a list of books and are asked to select one related to wellness to read for the assignment. Chris identified that the books on the list were narrow in focus and perspective. Most of the books were written by professional coaches and focused on sports, which wasn’t representative of the professional interests or experiences of students in the Collaborative AAS program. This became the action plan for the semester: to create a more inclusive list of books for students to choose from. We worked with a campus librarian to identify books available to students throughout the program’s partner campuses that would provide diverse voices, perspectives, and lived experiences related to the topic of self-growth.

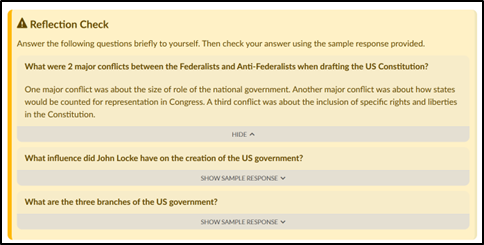

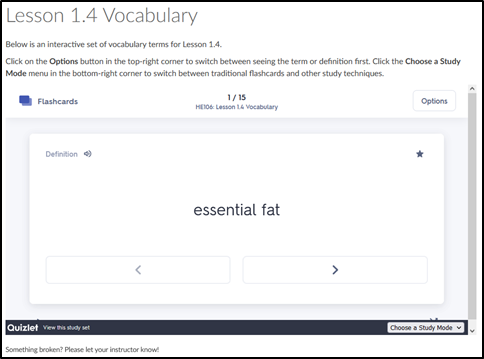

Along with updating the list of books, we updated the design and layout of the assignment page. The books were organized thematically, annotations for each book were provided, and callouts were added to highlight which of the nine dimensions of wellness each book related to. So not only were the books more diverse in perspectives, but those perspectives were the categories by which the books were organized, making it easy for students to find the books that they were most interested in.

The amount of time it took to make this update was low, and now students have a list of books that represent a more diverse range of voices, lived experiences, and perspectives.

Image 1: Screenshots of Self-Growth Book Review instructions page on Canvas. Book titles are organized by the perspectives they take on wellness and growth.

Using the EDI Reflection Document

The reflection document was created to be easy to use for instructors and instructional designers. There are just three steps. Step 1 is to identify the strengths relative to EDI in your current course. The document lists many components of a course and how EDI can be incorporated into each. Step 2 is to identify the opportunities for making the course more equitable and including more diverse perspectives on the subject matter. Step 3 is to identify one of the opportunities from Step 2 and create an action plan for making that course component (and the rest of your course as a result) stronger.

When it comes to incorporating EDI into courses, the most important step is to pick a place and get started. Your instructional designer is here as a resource to help! Make it your new year’s resolution this year to make your course more equitable, diverse, and inclusive.