If you’ve ever tried to explain your work or research to anyone outside your field, you may have realized how much your discipline relies on specialized language that is often difficult for people outside your field to understand. To students, this type of language can be especially intimidating. And even more so when they aspire to join your profession or discipline and may not want to admit they don’t understand something.

But jargon doesn’t only occur in academia—it occurs across fields, especially in health and medicine where critical information often needs to be communicated to patients and the public. With this in mind, U.S. Congress passed the Plain Writing Act in 2010 to make public communications from the federal government clearer and easier to understand. But many of the plain writing techniques detailed in the 2010 Act can be used to make any type of writing clearer. In your courses, these techniques can be used to explain lengthy assignments, assessments, or discussion prompts. They can also be used for longer-form writing and media like presentations and scripts. Many of the techniques highlighted in this article are especially useful for writing online, where many readers often skim the page and look for what they need to know and what they need to do.

To put it simply, plain language is used to communicate complex topics to a broad audience in a digestible way. And it’s an important part of making online courses at UW Extended Campus accessible for all students. Here are some key techniques to write in plain (or plainer) language in your online courses.

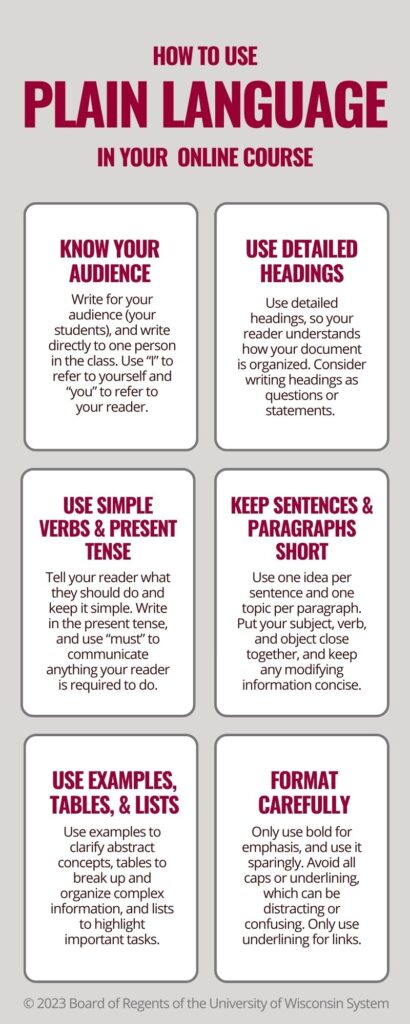

Know Your Audience

Write for your audience (your students), and write directly to one person in the class. Use “I” to refer to yourself and “you” to refer to your reader.

Use Detailed Headings

Use detailed headings, so your reader understands how your document is organized. Consider writing headings as questions or statements. To keep your headings accessible though, keep them under 120 characters in length.

Use Simple Verbs & Present Tense

Tell your reader what they should do and keep it simple. Write in the present tense, and use “must” to communicate anything your reader is required to do. For example, avoid “should.” Rather than telling students, “You should keep your paper under two pages,” say, “You must keep your paper under two pages.”

Keep Sentences & Paragraphs Short

Limit sentences to one idea and paragraphs to one topic. When you write a sentence, remember to put your subject, verb, and object close together, and keep any modifying information concise.

Use Examples, Tables, & Lists

Use examples to clarify abstract concepts, tables to break up and organize complex information, and lists to highlight important tasks.

Format Carefully

Only use bold for emphasis, and use it sparingly. Avoid writing in all capital letters or underlining, which can be distracting or confusing. Only use underlining for links.

If you’re interested in reading the complete guidelines, check out the Federal Plain Language Guidelines.

See Plain Language in Action!

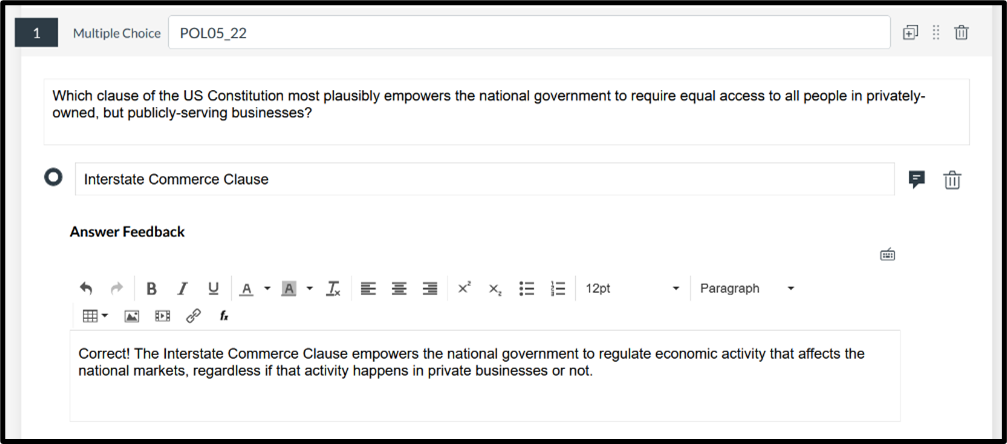

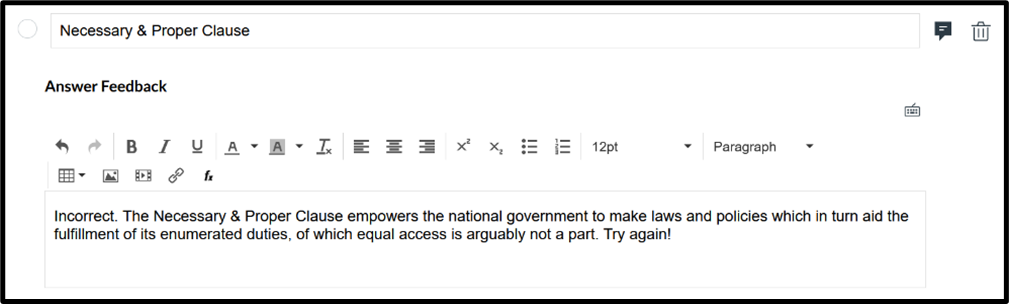

Here are two examples from an introductory marketing course that have been revised using plain language techniques. The first example is instructions for an essay assignment; the second is an excerpt from an instructor’s commentary. Both examples use some of the same techniques (notated in pink italicized text) to make the language clearer.

Original Instructions

As part of your academic obligations to this course and its field, expectations are that you write an eight- to ten-page essay using one-inch margins, double-spaced, 12-point, Times New Roman font, that examines a current trend in the marketing industry such as privacy marketing, micro-influencing, chatbots, social commerce, or another topic. Write 2000-2500 words.

Revised Instructions

In this course, you will write an essay on a current trend in marketing. Directly address your reader. → You may choose to write about privacy marketing, micro-influencing, chatbots, social commerce, or another marketing trend. ← Use consistent language. Use the same words to refer to the same things. Your essay must be 8 to 10 pages (2,000 to 2,500 words) double-spaced in 12-point, Times New Roman font with one-inch margins. ← Group similar information together.

Original Commentary

Consumers make many purchasing decisions, some rather unimportant day-to-day purchases, and some substantial and infrequent decisions. The amount of effort we put into making these decisions depends on many factors. For example, when you are choosing a snack to buy to take to a party, some factors you may not even be aware of that are part of your decision may include: How much can you afford to spend? Does an advertisement you’ve seen for a snack item come to mind? If no one likes your snack, will you feel embarrassed? Would you feel guilty for bringing an item you consider to be junk food if the people at the party are health and fitness oriented? On the other hand, would you feel awkward if you brought a health-food snack to a group that prefers beer and nachos? What if you’re taking the snack to a birthday celebration for an 8-year-old? Maybe you previously brought a certain snack to an event that was the hit of the party so you’ll return to the store to buy the same item without considering other alternatives.

Now that students have some understanding of consumer-buying processes, in the next module, they will be asked to author and submit a document in which they assess their own purchasing decision.

Revised Commentary

Consumers make many purchasing decisions. Some are routine, but others are rare and much more significant. ← Keep sentences short. Try to use one idea per sentence. This sentence was split into two separate sentences. The effort we put into these decisions depends on many factors.

Say, for example, you must choose a snack to bring to a party. You might consider the following questions:

- How much can you afford to spend?

- Did you recently see an advertisement for a particular snack?

- Will you feel embarrassed if no one likes your snack?

- Would you feel guilty bringing junk food if the group is health conscious? ← Keep language consistent. Use the same words to refer to the same things.

- Would you feel awkward bringing a healthy snack if the group prefers beer and nachos? ← See the above list item. These two items were revised to use consistent language.

- What if the party is for an eight-year-old child?

- If you recently brought a snack to another party that was a hit, would you buy the same item without considering alternatives?

↑ Use lists, so your information is easier to read. Also, make list items parallel in structure. All these items are questions.

Now that you have learned about how consumers make decisions, you’ll tell me how you decided to buy a product (or not) in the next module’s assignment. ← Directly address your reader, and use simple, clear words to tell them what they need to know or do.