It can be difficult knowing how to increase student motivation in your online course. But online learning has a ton of ways to raise engagement and students’ motivation! This article focuses on the ways that providing kinds of instant feedback can ensure your students are getting the resources and comments they need at the moment they need them.

How to Use This Article

Use the following article in the way best suited for your needs:

- Read just Step 1 if you want the most important information and a simple example. This is for faculty who just want the abstract or are looking for an easy way to improve their instruction.

- Also read Step 2 if you want to implement more advanced instant feedback on an assignment. This is for faculty who want to improve their quality of feedback and want more than the basics.

- Continue to Step 3 if you want to learn more about using instant feedback throughout your course, beyond just quizzes. This is for faculty who are open to changing different parts of their course. Your instructional designer can help you implement instant feedback in many parts of your course!

Step 1: Introduction to Instant Feedback

Timely feedback for students is integral to effective learning and students’ satisfaction with their learning experiences (Espasa & Meneses, 2010). Providing that feedback, however, can be more difficult in online classes. Although your lack of physical proximity to your students can be challenging, your feedback remains essential. It can be a powerful tool for motivating students through online courses, especially instant feedback (Bridge, Appleyard, & Wilson, 2007).

Instant feedback could include praise for excellent work, corrections of mistakes, or helping a student assess the quality of their work and assess the pace of their learning.

Instant feedback provides several benefits for students:

- Mistakes and misconceptions can be immediately corrected.

- Correct knowledge and skill application can be positively reinforced.

- Corrective feedback can be personal, which avoids embarrassing students.

- Students gain more self-awareness of strengths and gaps in knowledge or skill sets.

- Instant feedback can increase the amount of time a student is engaged in the course.

Two Types of Instant Feedback

In an online course, students can benefit from two kinds of instant feedback: instructor comments and norm-referenced feedback. Norm-referenced feedback is feedback students get by comparing their work or progress to other examples or standards, often created by the instructor. For instance, giving students an example of an exceptional essay to help them with their essay is providing norm-referenced feedback. Both instructor comments and norm-referenced feedback are common in coursework, though the latter form may not be immediately recognized as instant feedback.

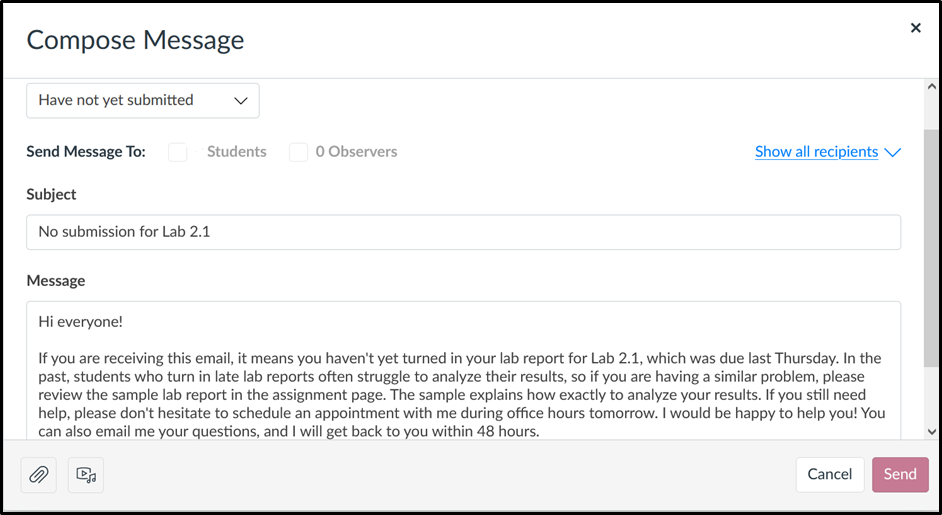

Instructor Comments

You can provide automatically generated written comments in response to specific answers or behaviors provided by students. For instance, when students choose an incorrect answer on a quiz, you can set up an automatic comment to provide the student with the necessary resources to fix their mistake the next time they need that knowledge (for example, in an assignment or exam).

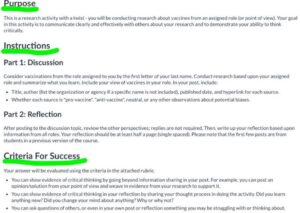

Norm-Referenced Feedback

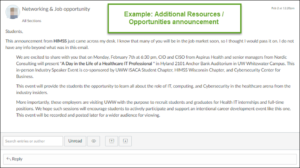

Students don’t just receive instant information from their instructors in the form of comments in response to answers. If you provide your students with norms for the class, such as deadlines, suggested timelines, and models of good work (and examples of poor work), they can compare their work and learning progression with those norms. They can instantly recognize when they are falling behind, need to improve their answers, or need to complete specific, upcoming work, all as soon as they need it.

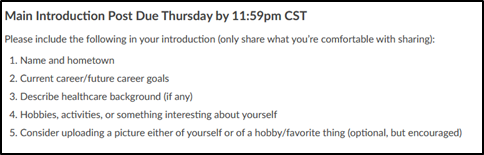

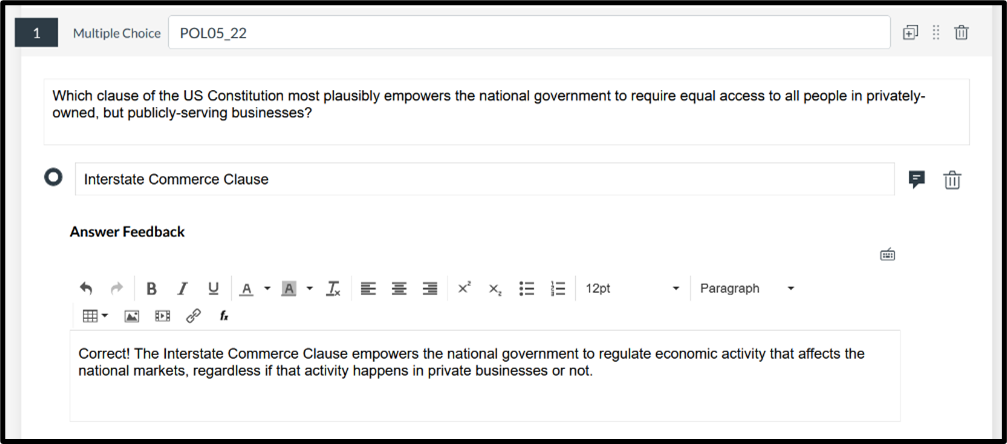

Example of Instant Feedback in Canvas

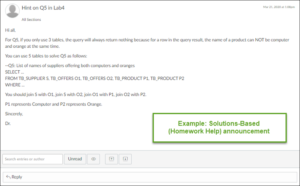

In this political science course, the instructor set up a Canvas quiz to automatically provide feedback based on a student’s answer. In the first image, the correct answer provides positive feedback.

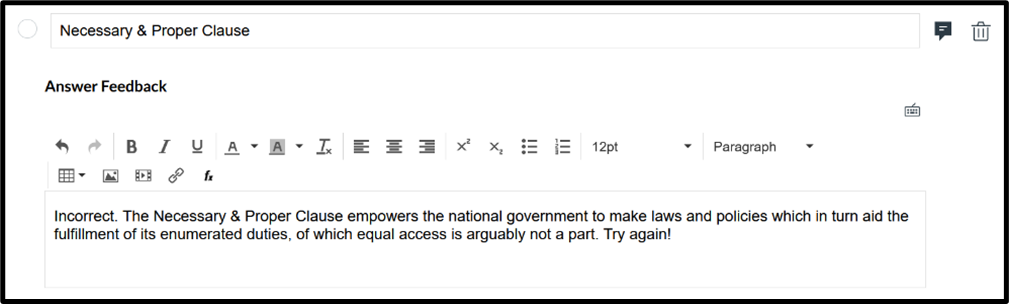

In the second image, an incorrect answer provides instant feedback as well, explaining the likely misconception that would lead a student to choose that answer.

Step 2: More Advanced Instant Feedback

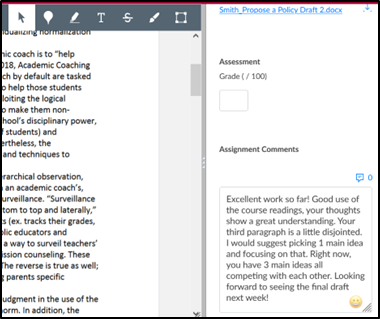

Thanks for striving to improve your feedback! While any helpful feedback is better than no feedback (Espasa & Meneses, 2010), there are ways to improve its quality and effectiveness. The third and fourth images below show more detailed feedback for both correct and incorrect answers, demonstrating the characteristics of effective feedback.