As part of serving the people of Wisconsin, UW Extended Campus strives to ensure every student, no matter what, can earn a high-quality and accessible postsecondary education. In service to this goal, the UWEX Instructional Design team and faculty work together to fix the common accessibility challenges faced by UW students. In fact, the UWEX ID team works hard to check our courses to address many potential accessibility issues before they ever become problematic. Checking images, HTML code, text, videos, language, links, and more is part of our process for every course.

What about your course announcements? We know things can change and you may need to share other learning resources or web links with your students in an announcement. While the ID team is available to lend a hand, we want you to feel confident in ensuring your announcements or other course updates are as accessible as the rest of the course.

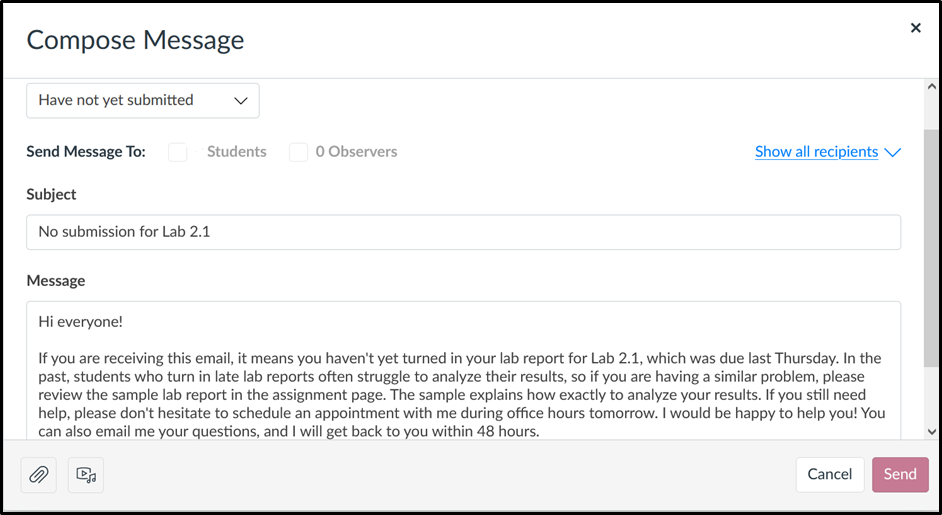

In the video below, see how three common challenges might appear in a course announcement, and how they can be fixed using the accessibility tool already integrated into Canvas. The rest of this article reviews some challenges beyond those addressed in the video.

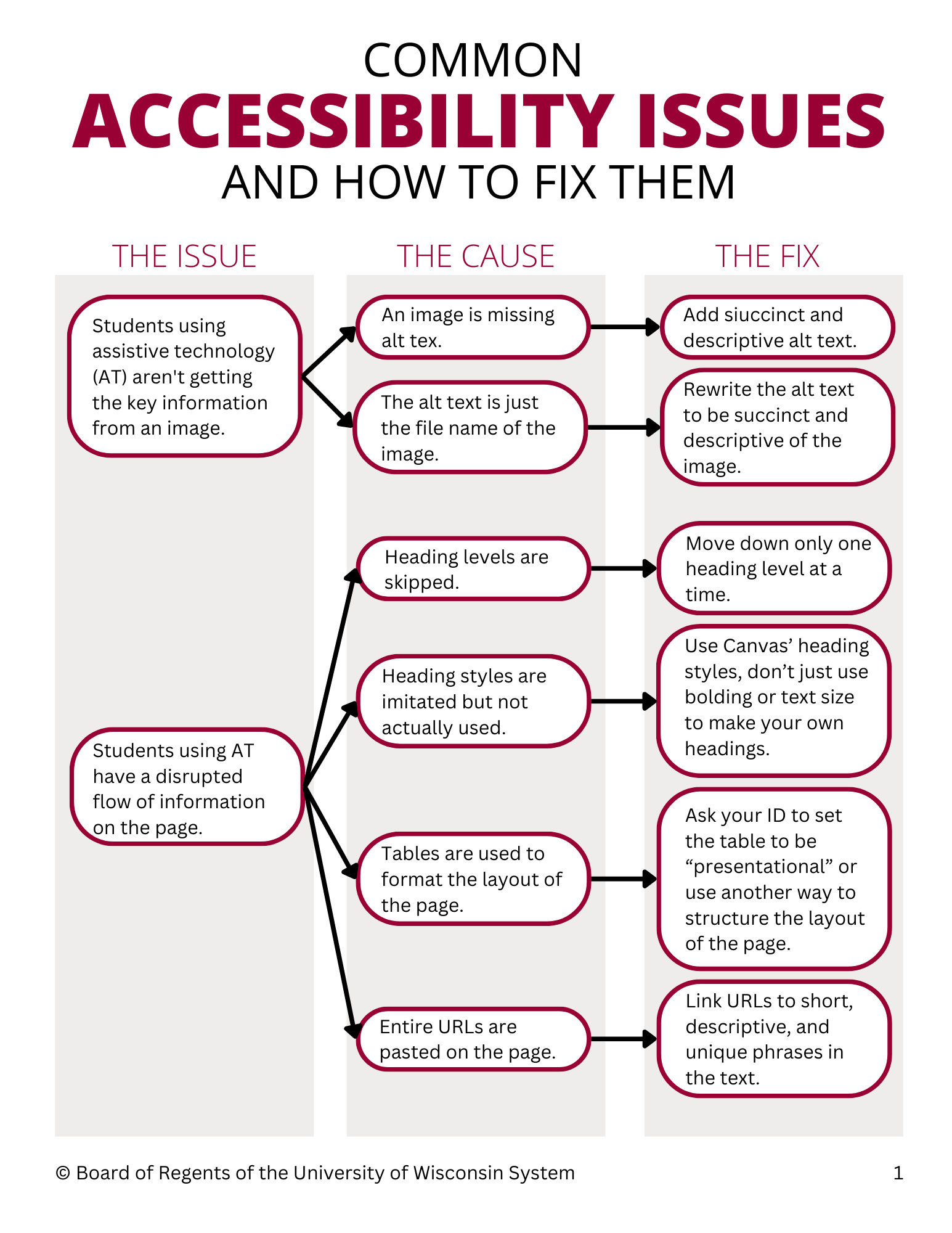

Further Issues, Their Causes, and How We Fix Them

There are several other accessibility issues that the ID team addresses during the design of a course. Check out how we fix the issues below.

Issue: Students who are deaf or hard of hearing aren’t getting the key information from a video.

The cause of this issue

The video likely doesn’t have a transcription or closed captioning (or the captions are inaccurate).

How we fix it

If there is a video as a learning resource, we need to verify that the video has captions or a transcription. Resources made with UWEX Media Services automatically have both. To resolve a lack of captions or a transcript, we might reach out to the instructor to either make them or find a new video.

Best practices

To make videos as accessible as possible, we comply with following best practices:

- Captions are best for videos while transcriptions are best for audio-only resources.

- If using auto-generated captioning, rewatch the video to check that the captions line up with the audio, there are no critical errors, and fix likely mistakes, such as names or acronyms.

For more information, visit the Transcripts page from the Web Accessibility Initiative as well as the Captions/Subtitles page from the Web Accessibility Initiative.

Issue: Students using assistive technology can’t distinguish links when searching through them.

The cause(s) of this issue

Screen readers will read all the text that is on the screen, including URLs, letter by letter (“h-t-t-p-colon-slash-slash-w-w-w-dot…”). Furthermore, screen readers can jump from link to link for easier navigation, but knowing the correct link to select can be a challenge if they all say, “Click here.”

How we fix it

We make each link on a page succinct, descriptive, and unique. Consider the differences between the following three examples:

- Here is the website for the Web Accessibility Initiative: https://www.w3.org/WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-intro/.

- Click here to view the Web Accessibility Initiative website.

- The Web Accessibility Initiative website has plenty of resources to help you.

The third example has the most accessible link because it is unique and concisely describes the link’s destination.

Best practices

For clear and accessible links, we comply with following best practices:

- Avoid phrases like “click here” or “read more.” Even if the student only reads the linked text, they should know exactly where the link takes them.

Issue: Students using assistive technology have difficulty finding the information they need on the page.

The cause(s) of this issue

In addition to the challenges described in the video, there are a few other reasons a webpage can be inaccessible. One is an inefficient or clunky presentation of information. Just as an entirely written-out URL can disrupt the smooth reading of a paragraph or list, the use of a table to structure a page could prevent a logical interpretation of the page by assistive technology.

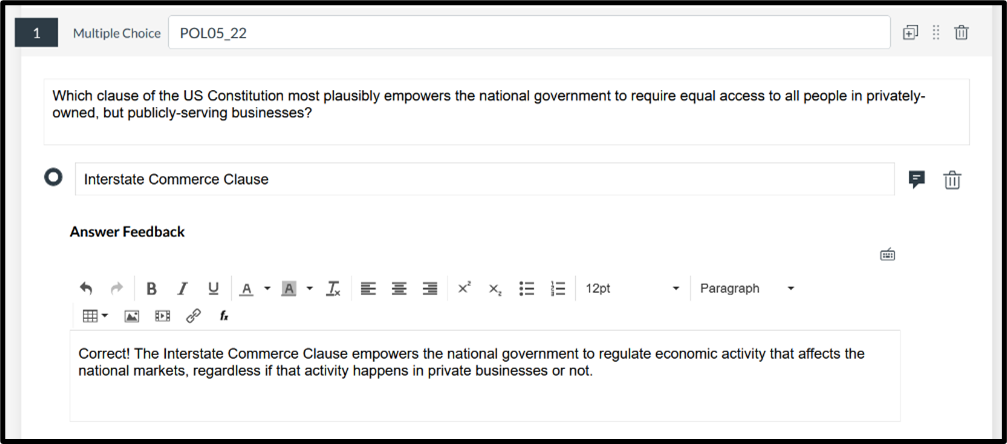

How we fix it

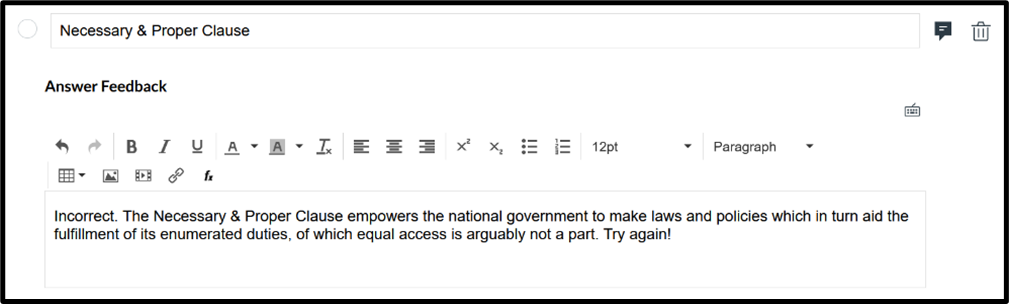

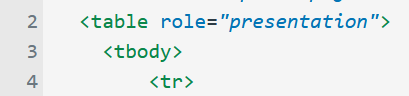

As mentioned above, w make sure links are succinct, descriptive, and unique. In addition, we check that tables are only used to present tabular data. If the situation demands a table to help us structure the page layout, we will change the HTML code to set the table to role=”presentation”, such as in the image below.

Best practices

To ensure the course’s pages present information undisrupted, we comply with following best practices:

- In the body of the text, write in short, clear sentences and paragraphs, and use list formatting as appropriate.

- When using tables to present data, include headers and a caption.